Going Steady

After decades of cinematography involving cameras on tripods, dollies, sliders, and cranes, the camera went mobile. Cinematographer Garrett Brown invented the Steadicam in the mid-1970s and it was popularized by two horror movies of the era: John Carpenter’s Halloween in 1978 and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining in 1980.

The Steadicam is a mechanical counterweighted stabilization device that allows a camera operator to move with a camera – without the shakiness usually associated with handheld camerawork. The camera is mounted onto a platform on a weighted pole that can rotate along several different axis. That platform is suspended by a spring-loaded arm, which is attached to a reinforced vest. The key to the Steadicam’s effectiveness is balancing the camera on the platform and the tension of the springs in the arm. With everything dialed in correctly, the camera will “float” in front of the operator. A skilled Steadicam user can walk smoothly and adjust the orientation of the camera on the fly. This allows the camera to travel in ways that were impossible before –through doorways, down hallways, up and down stairs – in a smooth, cinematic way.

The following clip from The Shining is one of the classic examples of brilliant Steadicam work. Garrett Brown himself was heavily involved with the cinematography of the film, helping to create custom rigs for Kubrick’s complex shots. The Steadicam was used most famously to follow the character Danny as he explores the Overlook Hotel on his tricycle, but it was also used as a replacement for the kind of tracking shots that would normally be done on a dolly or slider. The “floating” camera is especially effective in The Shining precisely because it moves in ways that should be impossible – it gives the impression that we are seeing the film through the perspective of one of the hotel’s restless ghosts.

Halloween also used the Steadicam in an exciting new way, most notably in its opening sequence. Carpenter utilized the technique to give the camera the perspective of young Michael Myers as he commits his first grisly murders. We even see the child’s hands as he retrieves a knife. The camera work in this sequence isn’t nearly as smooth and “floaty” as that in The Shining, but it matches the gait of the child walking through the environment. This sort of smooth point-of-view cinematography was revolutionary in 1978 and would have been impossible before the invention of the Steadicam.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnWw060ygG8&t=77s

Here’s an interesting historical artifact: the 1978 test footage created for the opening sequence of Halloween. At the time, the Steadicam was known as the “Panaglide” and had only been used on three other films.

Steadicams changed the way the cinematographers create moving images. They were – and still are – used on features, commercials, television, and even broadcast journalism. However, there are limitations to what you can achieve with a Steadicam: they are heavy, awkward, and require a very skilled operator. When you operate a Steadicam, you need to walk smoothly and evenly and you have to manipulate the camera carefully. The process of balancing a camera on a Steadicam is also time-consuming – and failing to do so correctly will result in poor performance. These issues aside, the Steadicam completely transformed film movement – and paved the way for innovations to come.

Gimbal Revolution

About five years ago, a new technology began to emerge in the world of filmmaking: the three axis gimbal. A gimbal can be used to achieve many of the same shots that had been captured on a Steadicam – smooth running, transitions between locations, traveling up and down stairs – but they also opened up an entire realm of new possibilities.

A gimbal works by using three motors to keep a camera level along the pan, tilt, and roll axis. Larger gimbals generally suspend the camera in a sort of cage with a two-handle grip above. The camera can be “steered” using the handles, but the normal shakes associated with handheld work are smoothed out. A gimbal does not remove “up and down” motion, although a gimbal can be mounted to the spring arm of a Steadicam to help with this. The camera still needs to be balanced carefully in the gimbal – the better balanced it is, the less work the three motors have to do – but this process is generally faster and easier than balancing a Steadicam.

Gimbals allow creators to film smooth movement with a more compact device that is easier to use with less training. Because a gimbal is not physically attached to its operator, it can be passed from one person to another, or through spaces that would be otherwise inaccessible. On one shoot for the advanced production class, we passed a gimbal from an operator to a special rig on a small crane. Because they are electronic, many gimbals can also be operated remotely – one person can move the unit through a scene and another can point the camera in the right direction.

From the very beginning, filmmakers used gimbals to craft shots in dynamic new ways. The scene below was filmed by Vincent Laforet back in 2013 as part of a short film meant to show off the (then) new technology’s potential. To achieve the shot, a camera operator on roller blades chased a taxi, which the actor rushed into. As the car takes off, the operator holds onto the side and films through the window, then skates away backwards. A second operator assisted through a remote monitor. This kind of shot simply would not have been possible before the invention of the gimbal.

If you look at the behind-the-scenes materials for any major recent film, you’ll probably see gimbals all over the place. There are lots of examples in this featurette for Straight Outta Compton – in many of them, the camera is passed from one operator to another or from a rig of some kind to an operator.

In the last few years, this technology has gotten cheaper, lighter, more capable, and much more widespread. The latest gimbal in our collection is the DJI Ronin S, a single-handed gimbal that can carry a payload of up to seven pounds. Check out the following promotional short film (and making-of video) to see what it can do.

What’s Next

I think that both gimbals and Steadicams will continue to be used for a long time. Gimbals in particular are starting to reach a stage of mainstream adoption that were never seen on their more expensive and complex mechanical ancestors. You can now buy a three axis gimbal for a cell phone for around a hundred dollars. However, Steadicams are still common on the sets of major productions – they can hold more weight and there are a lot of skilled Steadicam operators who can achieve amazing results with non-electronic stabilizers.

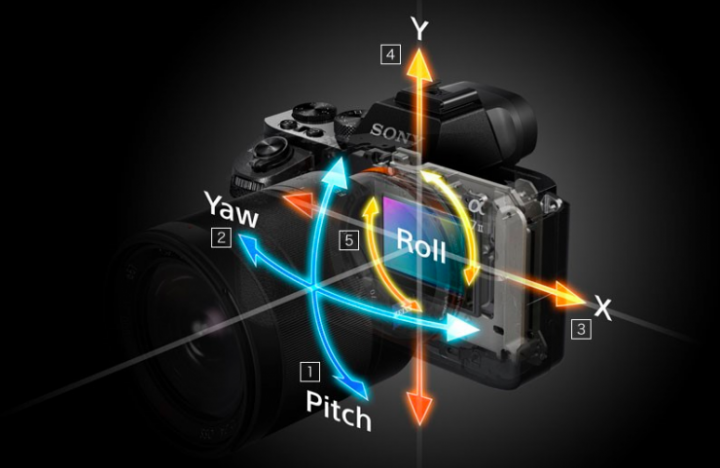

The next evolution of stabilization technology is taking place within the camera itself. We’ve had lenses with built-in image stabilization for a long time – it’s been used to take out the tiny jitters that come with handholding a camera, especially at a longer focal length. Image stabilization in the body of the camera works by actually moving the sensor to compensate for small movements. This is sometimes referred to as IBIS, or In-Body Image Stabilization. Sometimes, this is further enhanced electronically, by cropping in on the image slightly.

IBIS has improved the image stabilization capabilities of some cameras to the point that a gimbal is not always necessary. Panasonic, Fuji, and Sony are all using this technology and I think it will see more widespread adoption in the next few generations of hybrid cameras. The latest camera from GoPro uses a feature called HyperSmooth, which seems to be a combination of electronic and sensor stabilization, with some really remarkable results.

This technology is still developing, but it is very promising. Eventually, we may reach a point where completely smooth footage can be captured without any external stabilization – no gimbal, no Steadicam, not even a shoulder rig. I can only imagine the kind of impossible moves that we’ll be pulling off then.